![]() Esprit de corpses

Esprit de corpses

Three dead cars rose

phoenix-like from fire and crash damage

to become one prize-winning Lotus.

CLASSIC CAR Magazine, June 1994

by Arnold Wilson

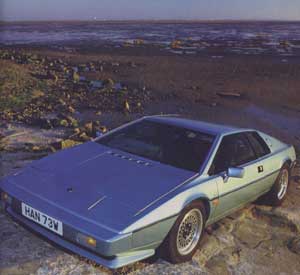

Mark Atkinson's beautifully rebuilt Lotus Esprit is a 1980 S2.2. Mostly. It's hard to believe, looking at the car now, that it was built up from two burnt-out Esprits and an insurance write-off. Yet it is complete in every detail, superbly finished both inside and out and runs beautifully.

'In 1986 I saw a burnt-out Lotus Esprit S1 advertised in Derbyshire,' recalls Mark, 'so we went down to see it and bought it for £300. It stood in the garden for over a year! I then bought an Esprit S2.2 which was also burnt-out, particularly at the front, although all the mechanical parts except the engine were present.

'Finally I bought a badly damaged body from someone who was using the chassis to build a Lamborghini Countach replica. The bodyshell had suffered heavy offside damage, had a broken back, a damaged roof and no driver's door – so I bought it! The rebuild took me 18 months, working on average four evenings each week and most weekends.

'My car was basically built from the burnt-out S2.2,' explains Mark, 'and my first job was to unbolt and remove the remains of the body, after which I took out the transmission (there was no engine with the car) and suspension until I got down to the bare chassis. I thought it was going to be reusable but closer examination revealed it had been slightly distorted by the heat. I decided to buy a brand-new one from Lotus – galvanised with a seven-year guarantee and costing £700.'

Mark built up the rolling chassis to act as a jig for the damaged bodyshell. The front suspension was rebuilt with new bushes – the wishbone ones proved particularly tricky – and Armstrong dampers. The uprights were reconditioned and new wheel bearings fitted. Mark installed a reconditioned steering rack.

At the rear end, large alloy castings house the wheel bearings and are located by semi-trailing arms, lower radius arms and compact coil spring/damper units. The fixed length driveshaft functions as the upper suspension arm.

'I replaced all the Ujs in the driveshafts,' recalls Mark, 'and all the bushes, including the large one at the front end of each semi-trailing arm. I fitted new rear wheel bearings and torqued them up to the specified 200lb-ft but there was still some play and, despite checking the specification with Lotus and even fitting a different make of bearing, the problem persisted. It was only solved when an engineering friend machined out the housing and put in a set of taper roller bearings.'

The braking system – 10.5in solid discs at the front and 10.8in inboard discs at the rear – was completely rebuilt using reconditioned calipers all round, new rear discs, Kunifer tubing and Aeroquip flexible hoses. The master cylinder received new seals but the servo was in good order so remained untouched.

The handbrake system is unusual: the lever is on top of the glassfibre inner sill at the driver's right hand, while the linkages and sections of the twin operating cables are completely concealed inside the sill. It's not uncommon to find Esprits with a large hole cut in the underside of the sill to give access. Mark overhauled the system, putting in a pair of new cables before sealing them within a new outer sill.

The gear linkage came in for some attention: 'It consists of a three-section rod and a single cable which moves the selectors across the gate,' explains Mark. ' The jointed rod runs from the gearlever, down the side of the engine and eventually into the gearbox. I put in new bolts and bushes and because some of the components are hidden inside the chassis and impossible to get at once the body has been put back on, I set up the adjustable rack very carefully indeed, following the Lotus manual to the letter. People often complain about the awkward gearshift but mine works perfectly well.'

With the rolling chassis completed, Mark was ready to put the damaged bodyshell on and square everything up before starting the extensive glassfibre repair work. The Giugiaro-designed body was first shown as a design exercise on a stretched Europa chassis in 1972; when it was launched in 1975, the Esprit was streets ahead of its predecessor in space, luxury – and price.

Using the chassis as a jig, Mark carefully shimmed the body so that on bolting down it would not be distorted. Most people – even hardbitten enthusiasts – would not have attempted to repair the damaged bodyshell, but Mark had little choice, as a new body at £4,000 was just too expensive to contemplate.

With the body firmly in place, the damaged areas, including the lower half of the windscreen pillars and all the bodywork around the lower A-post and wheelarch plus a large section of the floor, were all cut out. The B-post had also been badly damaged and was cut out, as were sections of the roof.

The amount of work involved in rebuilding the bodyshell was immense. While in some areas, such as the A-post/wheelarch, Mark managed to obtain usable sections from the crashed car, other parts had to be fabricated from scratch by taking moulds from an undamaged car.

Mark also had to make a new plywood bulkhead which separates the cabin from the engine and adds torsional rigidity to the body. Glassfibre bodies are repaired by buying the required area, such as mid, full or quarter front, cutting it very accurately so that it butts up snugly to the original bodywork, the 'V'ing it back and glassing it into place. Considerable skill is required but, done correctly, the join should be invisible and just as strong as the surrounding bodywork.

The missing driver's door presented quite a problem. 'This was the most difficult job,' recalls Mark, 'even though I managed to obtain a reject door (just the glassfibre part) free from a Lotus specialist in Norfolk. The glassfibre needed a lot of work, and the complicated inner parts I either had to make or buy. For example, a new intrusion door beam and a new aluminium window frame were priced at £120 each from Lotus, while the window glass came from a glass specialist in Luton and cost around £40. The window motor I obtained secondhand from another Lotus enthusiast and the door seals came from Paul Beck, the trim people. In the end it all came together and I now have a perfect, fully operational door – but it was a very difficult and awkward Job.'

With all the body repair work completed, Mark decided to strip off the remaining paint and after considering using a heat gun or Nitromors, he finally opted to do it the hard but safe way, using a dual-action orbital sander. After some 80 hours' work the car was trailered to a local painter who sprayed the body using two-pack isocyanate Lotus Ice Blue metallic paint.

While the body was away being painted, Mark turned his attention to the engine, but as his S2.2 car came minus the engine, he had to use the 2-litre unit from the other car. The all-aluminium, twincam 16-valve 1973cc engine develops 160bhp at 6500rpm and 140lb-ft of torque at 5000rpm, and is fed by a pair of Dellorto 45 DHLA carburettors.

With the help of his friend Mike, he rebuilt the engine with new rings, main and big-end bearings plus associated oil seals. Pistons, rods, camshafts and valves were reused. A new camshaft belt and a rebuilt tensioner completed the job.

The Citroën (ex-SM and Maserati Merak) transaxle was rebuilt with several new bearings and a new crownwheel and pinion. On running the engine in gear, however, with the rear end of the car jacked up, Mark was not too happy with the sound of the gearbox. It was removed and rebuilt again by a local Esprit specialist and it's been running well ever since.

After more than his fair share of bad luck and frustration, Mark's fortunes changed when he obtained carburettors, starter motor, alternator, instruments and panel, wiring loom and all the interior trim (except the seats) from a 10,000-mile written-off Esprit – and all at the bargain price of £210. Mark had his own car's seats recovered with black leather facings and vinyl backs.

'The glassfibre work was undoubtedly fiddly and time consuming but I actually enjoyed doing it,' recalls Mark, 'but the most disheartening moment of the whole restoration was when I realised that the gearbox and final drive would have to come out again. Everything was in place by then and I thought I was home and dry. I was tempted to put the car on the road but resisted – thank goodness!'

The complete car looks absolutely superb, with none of the ripples or surface imperfections of some glassfibre-bodied cars. The even shut lines and great attention to detail finish reflect the determination, perseverance and sheer mechanical ability of Mark, who did most of the work single-handed.

THE OWNER

My boyhood hero was Jim Clark and I've always loved Lotuses', says 36-year old Mark Atkinson, a flight test engineer with British Aerospace. 'I saw Giugiaro's styling exercise which became the Esprit in a magazine in 1972, and I was determined I had to have one. I started looking in 1990 but the only cars I could afford were junk, so I decided to build my own, that would be right. I had put a crashed Spitfire back on the road when I was 16, but had never undertaken a full rebuild before. Now I'm thinking of taking on an early fixed-head E-Type!'The Esprit is great to drive – it keeps well ahead in modern traffic. The chassis is responsive, it handles nicely and I've never found the limited; it's very quick and the economy is good too. When you first drive one, you're stuck by the poor visibility to the rear and an awareness of the mass of engine behind you giving a different handling balance. The steering feels dead until you open the car up. I've fitted Essex turbo wheels with 195/60 and 235/60 VR Goodyear's, which enhance the handling – but I'm still looking for the unique Lotus wheel centres for these! Fitting Nissan fans has helped to reduce the danger of overheating, but you do have to watch the temperature gauge all the time.

'My partner Helen loves driving the car too, though she finds the nose difficult to place when parking. One thing I don't like about the car is other people's reaction to it when driving, not helped by its James Bond connotations: I drive it because I like the car, not its image, It's very wide too – much wider than other road users think!

'The early road tests complained of excessive noise, but mine isn't at all bad. I used rubber washers on everything mounted to the body; principally to prevent water leaks, but I think it's suppressed noise well too. Esprits are full of shims – engine, gearbox, suspension, body, even the steering rack – if you don't get them spot on it ruins the car.

'The rebuild took 18 months; the car's one of the family now and I could never sell it.'

|

|