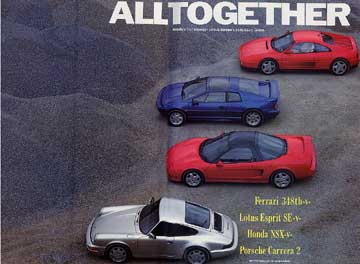

All

together now!

CAR– October

1990 by Gavin Green

If you can beat them, join them. Fresh from whipping Ferrari, Porsche and Lotus on the track – which the ad-men keep telling us is the 'ultimate' challenge – Honda now wants to join them on the road. And why not? Despite the magic names, engineering finesse, and all those years of tradition and hype, there is no sensible reason why Honda – replete both with cash and talent – can't try to tackle the supercar sacred cows.

It has gone about building a supercar in a different way from Ferrari or Porsche or Lotus, as you'd expect. You can bet that the new NSX, Honda's and Japan's first supercar, cost many times more to develop than Ferrari's equally new 348. And you can bit it will earn its maker less money (if any at all), for profit is not the point of the NSX. It's all about image; all about cashing in on the success of Honda's formula one programme, and making the world view the Civics and Concertos and Accords in a new, more respectful light.

How can the NSX be as profitable as a 348, when it costs about £15,000 less to by in Britain (£52,000 versus £67,499), and yet is built of more costly materials (an aluminium alloy monocoque and body, plus absolutely gorgeous forged alloy suspension components) and has more high-tech mechanicals?

The Ferrari and Honda are the new cars here, but who would dare dismiss the two old-times? The 911 may well be the oldest sports car in the world but, for most of its 26 years, it has been, in my view, the best. And just a year ago it received the most comprehensive revamp in its history. Many new body panels, a brand-new engine (but still a flat-six, still air-cooled), yet all the old-time charm. It's still not bad value, either, at £45,821 (even if, as with all Porsches, it's much cheaper in most other markets).

The Esprit made its debut back in 1976, was improved by a turbo engine in '81, and competed hard with the Ferraris and Porsches for a while. Then its act floundered in the mid to late '80s, shackled by insufficient development funds. But, just over a year ago, the financially revitalised company (bought by General Motors) announced the SE variant, the best Esprit of all. And one of the fastest supercars ever: offering Countach-busting performance, now for £44,900.

Deserted Durham Moorland Road, bright sunny day, Ferrari 348tb underneath you. What better, more invigorating way to travel? The quad-cam 3.4-litre 32-valve V8 engine, good for 300bhp, and just a few inches behind you, serenades with its magic; the little yellow Prancing Horse shield on the steering wheel boss does a jig on the bumps and undulations, animate like the rest of the car; and all around you is the most gracefully simple cabin you'll ever sit in.

It is not like driving a normal car: this is the charm of a Ferrari. Always has been. There is a delicacy, an intimacy, about the car. You can feel the cogs mesh when you change gear. You can sense the pads biting the big discs when you push the middle pedal. The right pedal is even more responsive: a millimetre of throttle movement means a discernible difference in speed, a quantifiable change in that wonderful engine note, which always rides with you – always reminding you (even when you may want peace and quiet, such as on a long run) that you are driving something quite different from a Ford or a Vauxhall (or a Honda).

The keen throttle response is crucial to the car's character. Apart from the 911, the Ferrari is the only car here that can really be steered on the throttle (aided by its short wheelbase, which helps a car's propensity to change direction quickly). Turn into a corner, using the steering, and the throttle control can fine-tune the attitude of the car. If the nose is running a little wide (unlikely, for the Ferrari has the best turn-in of the group), you can adjust it by backing off. Want the nose to run a little wider? Simple: squeeze on more power, and observe the whole handling composure change. The throttle of a Ferrari does so much more than merely make it go fast.

And then when it's over, when you've driven the Ferrari hard and fast, when you have enjoyed a moment of driving pleasure rare in today's sanitised world, you can get out and just look at the car. It's a piece of sculpture, a thing of beauty. Try as the others do, no-one can make a supercar as beautiful as the Italians. The 348 is one of the loveliest Ferraris.

After driving the Ferrari, you won't believe that anything could be better. No other car, surely, can give that close conjunction between driver and car; or the intimate relationship between the car and the road. None of the others is a Ferrari. Who else but the Italians could make so expressive a machine?

Well, none of the others can; let's make that clear right away. Which is not to say, they can't win this comparison: there is more to a supercar's repertoire than the richness of the driving experience, important though that is.

The Lotus is not tied down to the road as tightly, and its turbo four-cylinder engine – which actually produces more straight -line urge than any other car here – is smooth and refined. But it has no music, no magic, and the throttle response of a turbo car is never good.

Porsche's 911 is the only German sports car on sale now with real spirit, real élan, partly because it's old, and was conceived before the Germans got carried away by science. But, characterful old car though it is, it doesn't serenade you with the same richness as the Ferrari.

What chance do the Japanese have of matching the vivacity of a Ferrari? They have certainly shown no signs of being able to breathe life into machinery before. Besides, how can Honda, maker of blue-rinse saloons, suddenly hope to produce a red-blooded sports car?

The Japanese can't pull their old trick – of measuring all the rivals, copying in some cases, refining in most of the others – this time. You can't measure a Ferrari's virtues, let alone copy them – any more than you can analyse Mozart's music or Shakespeare's plays and, thereby, hope to duplicate them. Some things cannot e measured: neither the Japanese nor the Germans have learnt this.

Okay, so the Honda isn't as much fun to drive as the Ferrari, either. So be it. But when you put your brightest engineers onto a project (and there are no brighter bunch than Honda's), employ your finest workmen to build the car in a bran-new factory, and come straight out and say, hang the cost, we are going to build the best supercar in the world, and we don't give a monkey's whether it makes money for us or not because it's jolly good to our image, you've got to take them seriously. The NSX may not interact with you as richly as the Ferrari. But that doesn't mean it's not as good. It's like comparing an online engineering degree with one earned at an on-campus college. An online engineering degree is still an engineering degree.

On that wonderful Durham road, drive the new Honda NSX. Power comes from a 3.0-litre, quad-cam 274bhp V6, enriched by variable valve timing and variable valve lift thus, on paper, offering terrific low-end tractability and lively big-rev performance – it's red-lined at 8,000rpm.

Feels like a normal car at first. No intimidation. You don't have to climb over a massively wide sill ( which helps duct air to the mid-mounted twin water radiators of the 348) nor do you have to climb down into the seat, having vaulted a high sill, as you do in the claustrophobic cabin of the Esprit.

If just feels like a normal car. A CRX almost, except you're sitting lower, and the windscreen is deeper, and the tail higher. You don't have to steel yourself, prepare yourself, for a new vastly different experience. You just get in (entry and exit easy), sit straight-ahead (none of the askew nonsense that the other three demand, thanks to the absence of front wheel-arch intrusion, adjust the steering wheel to suit (it's the only one with reach and rake adjustment) and go.

And go fast! Faster, on any winding moorland road, than the other three. Easier to drive fast, what's more. The softer and more yielding nature of the suspension (double wishbone all round, although unlike the Ferrari's prosaic steel set-up, the Honda's are by elegantly forged aluminium alloy arms) means the car has nothing like the Ferrari's nervousness on sinuous British moors – about the only public roads where, in this country, cars like this can be pushed hard.

Whereas the Ferrari feels fidgety, a little headstrong, the Honda just absorbs the bumps and crests and dips as it charges insouciantly on its way. Unless you take real risks, or unless you have the skill of a Senna, the Honda is the quicker A-to-B public road tool. And that surprised us all.

Yes, it floats a little more on the crests and, yes, its wheels don't enjoy quite the same close relationship with the tarmac that the Ferrari's huge and beautiful 17-inch alloys enjoy. And the steering – the least sharpe of all these cars, and the one that weights up most at speed – doesn't chatter to you the whole time, talking to you, blabbering away.

Mind you, like most hyperactive things, the Ferrari's steering can get tiresome. On long trips you may curse the 348's wrist-jarring character, and the slight high-speed nervousness, preferring a quieter, gentler companion.

But it's fast, this Honda. Seriously fast. In real terms, quicker that the Ferrari, both on public road and, as we discovered before venturing to Durham, quicker on the racing circuit as well. On the track, at Castle Combe, the NSX was the quickest of the bunch (best lap, 1min 14.4, compared with 1 min 15.3 for the 348). What's more, it was the easiest car to drive on the bumpy Wiltshire track. You could lap all day at the NSX's best time, no fuss, no worry, no danger of spinning off and bending expensive aluminium alloy bodywork on crude steel barriers.

Not so the Ferrari, It is much harder work, at the Combe, just as it is on a winding moorland road. It's firmer sprung, more of a racer, much more throttle-responsive, a car that wants to duck and weave. It has to be manhandled, quite physically, to make it go fast (heavy steering, heavy clutch, heavy slow-shifting gearchange, heavy brakes). It taxes and tests you. Drive the Ferrari fast – very fast – and you'll sweat. The Honda is easy. Impressively, antiseptically easy.

The NSX will understeer at the limit, in a safe, controllable way that will frighten no buyer (whether they be serious racers, or poseurs who want nothing other than a pretty set of wheels). Stray near to the 348's (very high) limits and you can just start to feel the rear – so well anchored down at medium-high speeds – getting pendulous. Push a little harder and you'll be doing a blood-curdling, no-holds-barred, oversteer slide which will look wonderful (if you don't lose control) and feel wonderful (if you don't lose control). And while all this excitement is going on, the Honda will be going just as fast, in its unexciting understeering way.

On a less bumpy circuit than Castle Combe, the Ferrari would almost certainly have matched the Honda's lap time. The asperity of the Castle Combe surface upset the nervous disposition of the Italian car: its steering kicked our wrists, and it seemed to be darting around, nervously and uncomfortably, even on straights. Its very firm suspension – the Ferrari has noticeably less body roll than its rivals, and the biggest tyres – does it no favours at a circuit like Combe. You can tell the car has been set up for Ferrari's glass-smooth test circuit.

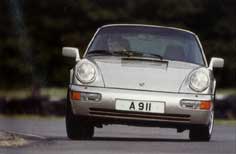

The Porsche got nearest to matching the Honda's lap time at the Combe (best lap, 1min 14.9), and got nearest to matching the Ferrari's entertainment value on the Durham moors. What an extraordinary sports car the 911 is! Despite its age, and its unprepossessing mechanical layout (it is the only car of the group without a mid-mounted engine; instead its motor sits out the back, out there in no man's land, where no self-respecting modern engineer would ever consider siting the engine of a modern car), the 911 competes hard and fast against a brand-new Ferrari, and the mightiest effort yet from Japan's boldest car maker.

Its great virtue soon becomes apparent, then you take up station behind the wheel. It's small. How refreshing to find a supercar maker that realises you can have speed and presence without length and girth. But how depressing that Porsche knew this 30 years ago, but seems to have forgotten in now (judging by the Sumo-sized girth of its more recent offerings, such as the ungainly 928).

The 911 is actually slightly longer than the 348 (the shortest but yet widest car here), but almost 10 inches narrower. It is six inches narrower than the NSX. Less body width means you've got more road space to pay with: it's a big difference. On a narrow B-road, this Porsche has no peer. Even on the wider Durham moorland roads, its manoeuvrability, its lissomness, is entertainingly impressive.

As with both the 348 and the NSX, the 911 has a pearl of an engine. Capable of pulling from about 800rpm in fifth gear (the Honda can dig even deeper into its rev range), and yet perfectly composed when the rev limiter silences it just before 7000rpm (it feels as though it could rev much, much higher, were it allowed), the 3.6-litre flat six is the feeblest engine in the comparison (250bhp), but doesn't feel it.

The 911 is marginally quicker than the 348, in the standing start figures (0-60mph in 5.3sec, Ferrari 5.6; 0-100mph in 12.8sec, Ferrari 13.0). It's faster than the Honda too, which, despite its speed on the track and on the road, is the tardiest off the mark (0-60 in 5.7sec, 0-100 in 13.1). Next to the 348, the 911's engine feels the most throttle-responsive. There is absolutely no slack in that throttle pedal and, when you're tanking on, the car's cornering attitude can be beautifully manipulated by the accelerator pedal.

Next to the Ferrari's, the Porsche's steering is the most communicative, the one that delivers the richest messages to the driver. What's more, it's better damped than the 348's, doing without the kickback and frenzy. With just over two turns lock to lock, it's the highest-geared set-up too. Don't let the power assistance standards ware on the Carrera 2, put you off: although a useful adjunct at parking speeds, it deadens none of the high-speed sensations.

No car is better made, either, although the Ferrari – beautifully solid and superbly finished – comes closest. The Honda is not quite as good, and, during our week-long test, was the only car to give trouble: it ran on five cylinders for a bit, and its traction-control system (one of the many technical novelties of this most technically intriguing car) started to misbehave, before correcting itself.

The 911 has the best brakes. Apart from the Ferrari, they have the most feel, and they stood up to fast laps of Castle Combe with greater decorum than any rival (the Honda's are closest for fade-free behaviour).

Next to the NSX, the 911 was also the easiest car to punt on the racing track, and on those sinuous Durham moors. It is a forgiving car, unless conditions are damp (when all that weight over the tail can betray it). It has the best ride quality, marginally edging out the Honda (the Ferrari is easily the firmest: the Lotus is supple yet noisy when wheels drop in and out of holes). The steering: the throttle response; the excellent grip; the terrific visibility (top marks here, although the NSX and the 348 are not far behind); the wieldiness. They all add up to make the Porsche a fast and easy high-speed drive, as well as an exhilarating one.

But the Porsche has one serious shortcoming, compared with the Ferrari and Honda. Pressing on, it feels less stable. It rolls more, it feels more on tippy toe, its front wheels have less of a grip on the road. And, at very high speed, the Porsche gets light at the nose. It gave one of our testers a helluva scare on the high-speed bowl at Millbrook, where we did the performance testing. It's a corollary of that rear engine, of course.

The Lotus has its engine in the right place, but it doesn't have the right engine. A good turbo (and by turbo standards, it is good) just cannot hack it with three of the finest normally aspirated engines ever made. True, it revs briskly and smoothly to the 7300rpm red-line. And it packs a mighty wallop – all from 2.2 litres and only four cylinders (it's good for 264bhp). But it matters little whence in came; what matters is how it goes.

Drive hard on a public road, and the engine drifts on and off boost, denying you the instant acceleration always available in the other three. There is far less engine braking, too, another corollary of turbo engines – and that means you cannot delicately balance the car's handling by using the accelerator pedal. To boot, the gearchange is easily the worst of the four (our test car, not the finest Esprit SE we have tested, had really vague shift) and the engine got boomy on the motorway.

More surprising is how far behind the others is the Esprit's chassis. On Castle Combe, the car understeered badly when pressing on; the main reason its lap time was the worst (best: 1min 15.6). On the Durham moors, the front end never felt securely tied down, the steering feeling peculiarly lifeless. The brakes felt dead, although they worked well enough. It just didn't compete, this Lotus, in any area other than straight-line urge (0-60mph in 4.7sec. 0-100mph in 11.9 – the best of the bunch). Given all the nice things we've said about the SE, this car was a major disappointment. It finishes a poor fourth in this comparison.

Less disappointing was the Esprit's interior, if only because we already know this was pretty awful. The Lotus gets plenty of leather – although it's not of the same quality as the Ferrari's Connolly hides – and seats which look inviting, once you can get into them (access is horribly limited, owing to the insufficient sweep of the door, and to the high sills you have to hurdle). But what really spoils the show is the appalling quality switchgear, no better than you'd get on an average kit car.

The door handles come from an Austin 1800, the column stalks have a second-rate feel and action, and the VDO instruments are too small, and badly sited. The walnut facia also looks rather tacked on: token arborealism, a crude attempt to give the cabin more class. Inside, the Esprit shows its age.

So does the Porsche. The 911's cabin is easily its weakest suit – an important consideration, after all that's where you'll be spending most of your time in this car's company. The seats look cheap and lack both lateral and thigh support, the dashboard is a mess (you have to grope for some of the fiddly switches, scattered willy-nilly all over the cabin), the steering wheel doesn't look anything special (although it feels nice enough, as is well sized), there is no left foot rest (a major omission on a performance car), and some of the trim standard is dire (most prominently that awful Elastoplast that is the roof lining). Given so much of this car was changed during its metamorphosis into a Carrera 2 last year, why didn't the Stuttgart engineers do anything about the car's most glaring weakness? At least the switches and the whole cabin have chunkiness and a solidity rare today.

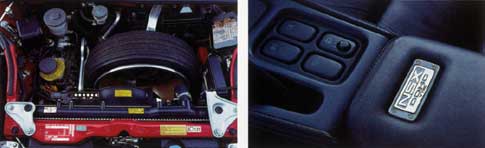

The Honda also has a disappointing cabin. Its dashboard has a nice sculpture, and the seats are easily the most comfortable and supportive of this group. The cockpit is roomier than the Ferrari's (although it lacks the 348's rear parcel shelf) and the Lotus's. And the pedals are perfectly place, good for heel 'n' toeing, well spaced, and supplemented by a wide left foot brace.

But the whole thing just looks so ordinary. You don't get those lovely hides of the Ferrari, which feel and smell so good. The leather you do get is the second-rate stuff, which may as well be top-quality vinyl. The dash is swathed in cheap-feeling plastic (don't be fooled by the genuine stitching), and the carpets are nothing special. The roof lining is cheap plastic, so disappointing on a car of this worth.

There's nothing wrong with the big, boldly displayed instruments – never mind that they look as though they're from lesser Hondas; many Ferrari switches are from Fiats – but there's plenty wrong with the satellite control pods, either side of the wheel. It's a variation of the Citroën CX theme and, like any copy of a wonderful original, is nowhere near as good. The arrangement looks messy, and is not easy to use. The hard plastic switches have poor tactility, as well. You just don't feel as though you're somewhere special, when you're ensconced in the NSX. It's a shame, because you are: this Honda is a wonderful car.

If I've sounded less than effusive about it so far, that is entirely intentional, it's a massively competent one, a car whose strengths can be rationally explained. They are many.

On most public roads, and on the race track, it is the quickest. It is the most comfortable car all round (best seats, and a surprisingly supple ride). It is the most restful on a motorway. It is the easiest and least demanding to drive fast, an utterly unintimidating mid-engined supercar that really could e used for shopping at Sainsbury's, were its boot bigger. It has the most benign high-speed handling, and is almost impossible to unsettle in sharp lift-off manoeuvres performed mid-corner. It is the most technically intriguing, and has the juiciest mechanical detailing. Those forged aluminium alloy wishbones are mechanical artistry. And it proved the most economical on test (23.0mpg; Porsche 21.6; Ferrari 20.2; Lotus 19.7).

There is no avoiding it: the NSX is a breakthrough, a supercar that furrows new ground. How can a car with so many compelling virtues be anything other than the best? It can't be. And it is. It's better than the Ferrari, and by some margin. And better than the 911, by an even bigger one. Honda has done a formula one, in the supercar field.

Yet, I just don't want one: it's not special enough. It doesn't look that good, to my eye: rather like a poor pastiche of a Ferrari. Honda's boldness seemed to have run out, when it came to the styling. But, much more important, driving the NSX just isn't enough of an event. By exorcising that lovely sensitivity and nervousness endemic in a mid-engined car. Honda has partly negated the point of buying a mid-engined car. It just doesn't interact with you richly enough; it doesn't bewitch you, intoxicate you, win you over, warts and all.

The 348 and the 911 do. They are special cars, and driving them is a special experience. You will savour every occasion you punt these cars hard on a deserted road, even if you may not be going as fast as the NSX driver. You many have to exert more effort, but so what? That's what sporting cars are supposed to be about. You have to drive the 348 and the 911, instead merely of letting a wonderful car do the work for you.

Of the pair, the Ferrari wins – if you can afford the extra 20-odd thousand pounds, and can wait five years to take delivery. There is nothing like it. It communicates so richly, involves you so completely. And, when you have finished driving it – cocooned in that exquisite cockpit – you can get out and feast your eyes on one of the loveliest cars ever designed.